History of a mining monument

Discovery of the exploitation

The discovery of the Carboniferous outcrop of Sotón dates back to 1792, when the naval engineer Fernando Casado Torres, sent by Carlos IV, recognized the Asturian basins in search of coal-stone deposits. It was not until the middle of the 19th century (between 1845 and 1865), when the Englishman Guillermo Partington, co-founder of the first gas company in Madrid, claimed for its exploitation several of the deposits that would make up Minas de Santa Ana, years later Grupo Sotón.

Start of Santa Ana mines

The Compañía Cantábrica de Santa Ana, founded by Partington himself and financially linked to Herrero y Compañía was the first company to exploit the coal deposits in the area. After its liquidation in 1867, its assets were sold to the Sociedad Hullera de Santa Ana, a french company linked to the Herreros. Years later, this company became part of the Sociedad Carbones de Santa Ana and finally, in 1877, the Sociedad Herrero Hermanos.

Santa Ana mines already had the Langreo-Gijón railway to sell their coals, but, above all, Santa Ana mines had coal demand from Duro y Compañía, which in 1859 had lit its first furnace in the neighbouring council of Langreo.

After the business restructuring of Duro in 1900 (Sociedad Metalúrgica Duro Felguera, SA or SMDF from then on) a change in strategy towards vertical integration was initiated, acquiring the Santa Ana mines in order to control the raw materials needed for the furnaces.

The need for more coal led Duro to take over other mining companies and modernise its operations and transport.

Switch to vertical operation

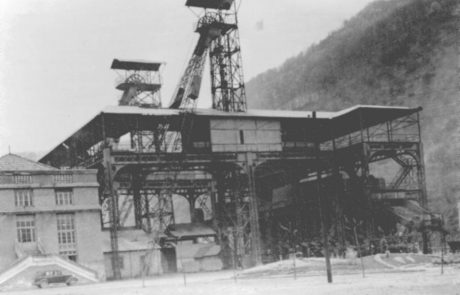

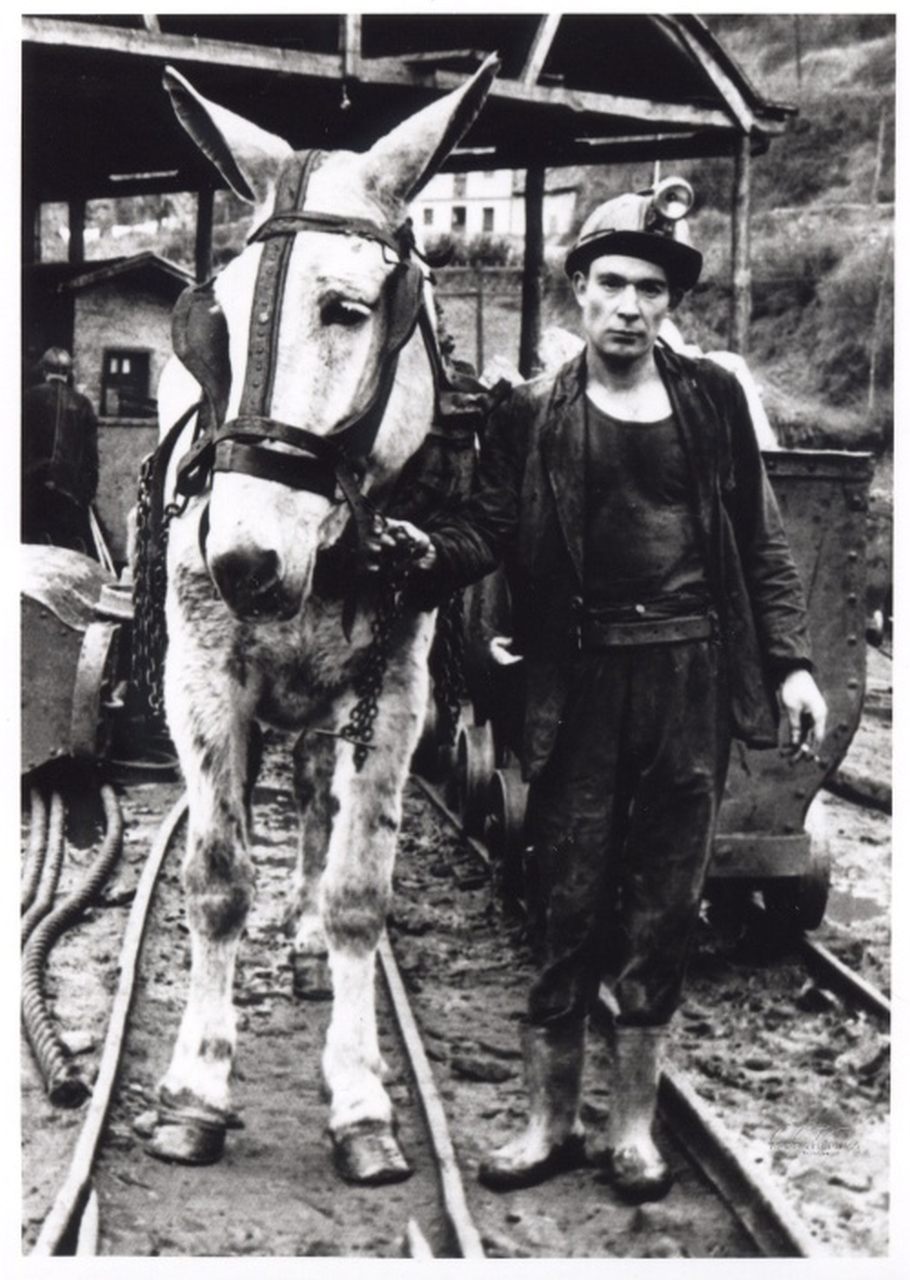

A substantial change was consolidated in the second decade of the 20th century, when the transition from traditional coal exploitation, mountain mining, to vertical exploitation by deepening in vertical shafts, was initiated in the Coal Basins.

This is the case of the Entrego and Sorriego Shafts in San Martín del Rey Aurelio, or the Fondón Shaft in Langreo, which was put into operation just two years before the Sotón Shaft by the SMDF.

Birth of Pozo Sotón (Sotón Shaft)

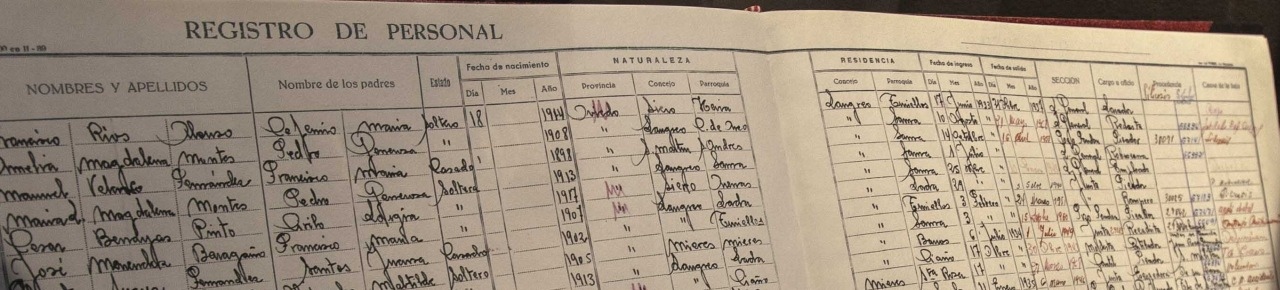

The preparation and deepening of the Sotón Shaft was carried out between 1917 and 1922, being necessary to displace the Nalón river. Its construction was carried out, by decision of Duro, exclusively with workers from the area. In order to take profit and free up the spaces close to this mine, some of its old pieces (pitheads) were incorporated as auxiliary elements of the vertical shaft (that is the case of Sallosa or Generala pitheads).

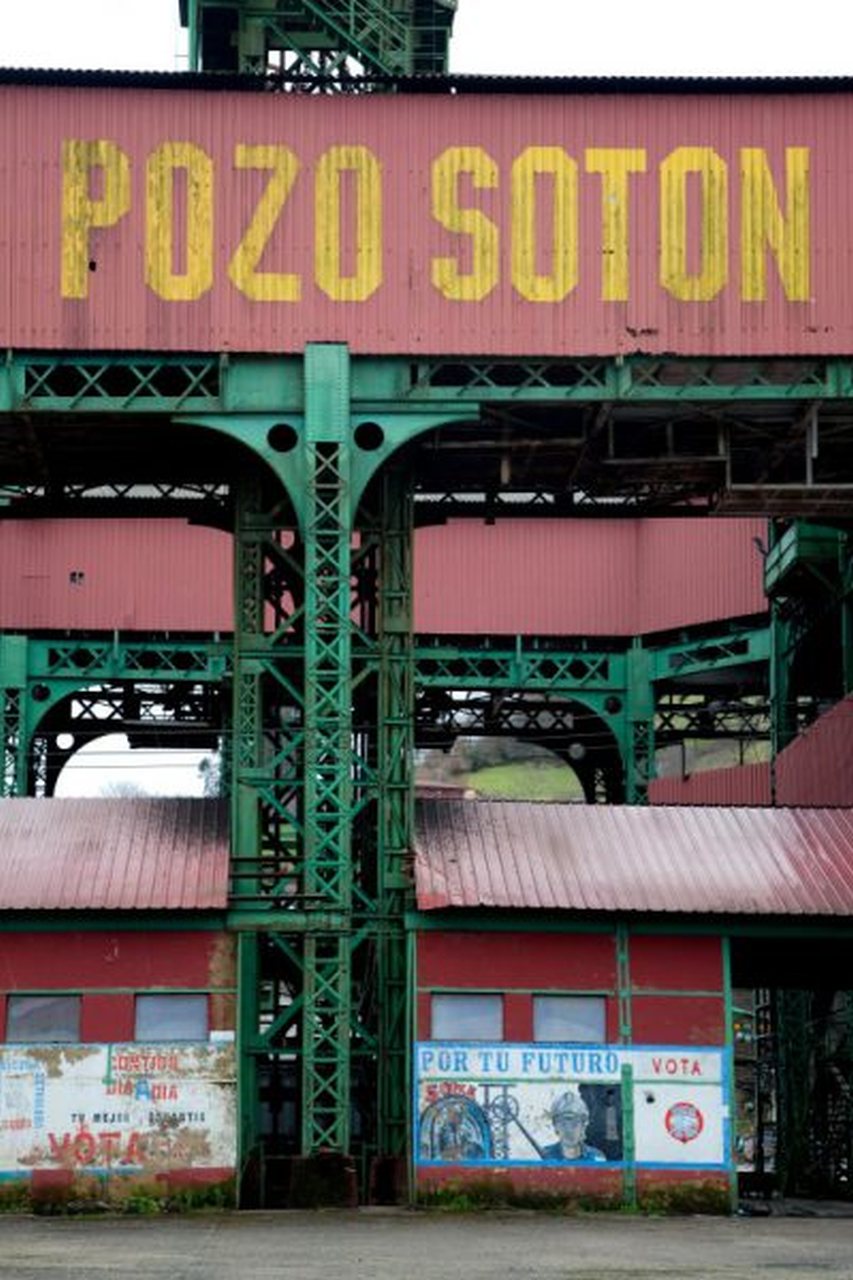

Throughout the 20th century, Pozo Sotón was subject to various extensions and modifications to increase its production capacity and efficiency, although always respecting the original concept. Since 1967, Pozo Sotón has belonged to the state-owned company Hulleras del Norte Sociedad Anónima (HUNOSA).

Asset of Cultural Interest (Bien de Interés Cultural – BIC)

On 1st February 2013, the initiation of the declaration of the Monument of Pozo Sotón as an Asset of Cultural Interest took place.

The International Committee for the Conservation of Industrial Heritage includes it among the 100 most representative elements of industrial heritage in Spain.

Finally, in 2014, several properties of the well are declared a Property of Cultural Interest with the category of monument.

The declaration includes the following items:

- the two headframes.

- the reter that surrounds the two headframes.

- the powerhouse and the union office.

The central structure

The central and fundamental piece of the well, is made up of

- the two metal headframes of rivets and welding, about 33 meters high.

- the reter or metallic structure of laminated profiles, which surrounds the derricks and houses the coal classification area, also assembled by means of metallic rivets and welding.

- the powerhouse and union offices, a brick building located in front of the foot of the headframes. The latter houses the Siemens Pulley Koepe extraction machines, which replaced the original ones, as well as the compressors.

The construction of these three elements goes back to the origins of the vertical shaft, between 1917 and 1923, when Duro Felguera prepared the vertical shaft of Sotón, remaining as such, despite some modifications and extensions as a result of the activity, until the present day.

The building of the engine room and the union office was modified in 1954, when Duro Felguera, in a context of increased investment through American credit, decided to expand it to increase the capacity of compressed air production. The growth in length of the building responded to the need to replace the obsolete compressed air generation equipment that was still the original at the time.

The extension of the building was planned with scrupulous respect for the identity of the property, maintaining the original style of the building.

Its development in length was planned on the south side, so that from then on reter and headframes were off-centre with respect to the layout of the powerhouse.

The reter

Perhaps the element of greatest formal and functional interest in this group due to its integrating function is the so-called “reter” or classification workshop. This involves the two headframes, as we have already said, integrating them into a single volume and partially breaking their mechanical and formal independence.

It has also supported interventions, evident in the whole structure. Originally there was no partial perimeter closure made of sheet metal that we can see today, which was installed to isolate the entire classification area from the weather.

The reter allowed the coal to be processed by gravity, before falling into the hoppers located above ground level where the company’s now defunct railroad arrived directly.

The indicated configuration of the productive nucleus with the three elements – derricks, powerhouse, union offices and reter – allowed a fluid and concentrated organization of the work outside, reducing to the maximum the proliferation of minor constructions that could hinder the normal development of the center of processing and transport of coal.